Greasies, fush and chups, shark and tatties, call them what you will, but for decades Aotearoa’s favourite takeaway has kept us from running on empty: every week Kiwis scarf down nearly six million servings of fish and chips – that’s 120,000 tonnes a year you greedy buggers. And with that in mind we thought it high time we delved deeper into this national phenomenon, so here is the result: the definitive guide to fish and chips, which is almost entirely 50% true – give or take.

Some scholars believe that the earliest reference to fish and chips can be found in preliminary sketches of The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci, which appear to show battered terakihi being served (to everyone except Judas Iscariot – who probably got one of those gnarly deep fried frozen crab sticks instead). Mention is also made of fish and chips in 1517 in William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, but due to political correctness gone mad this has been removed from the definitive Little Golden Books version of the famous play. Which is stink.

Fast forward to 1839 and British novelist Charles Dickens refers to a ‘fried fish warehouse’ in Oliver Twist, although the first documented reference in Aotearoa of what would become our national takeaway dish of choice is in a journal entry by Governor George Grey in 1864: “The country’s future hangs in the balance,” he wrote as fighting raged throughout the land, “and Mrs Grey’s chips are rubbish - wish we could afford the bought ones.”

The merits of ‘the bought ones’ – whether in regard to biscuits, cake, chips or haircuts – was, sadly, a sentiment that would echo dramatically down throughout the history of this nation. But the issue of the historical lineage of chips pales in comparison next to more important questions, questions that divide families, that define communities in the north and south of this land; tough questions that demand hard answers. The faint of heart may want to look away now.

First up, forget your who-shot-Kennedy-moon-landing-denial-tinfoil-hat-wearing hogwash conspiracy theories, let’s get to the nitty gritty: whatever happened to the crinkle cut chip? Supposedly developed to hold more sauce than the regular straight cut, ‘the crinkle’ saw its heyday in the late 80s together with big hair and the ‘hot chips in a bag’ boom driven by food trucks at sporting events and those vaguely depressing fairs favoured by rural New Zealand. The crinkle, when correctly fried, offered a degree of crunch and fat delivery never before seen in a chip, and in addition they looked really fancy. In short, crinkle cut chips, like Holden Toranas, impressed girls; because – like the Thunderbirds and flying cars – they were the future, they represented utopia and a brave new world. They were the shit.

But then, like ABBA T-shirts and hickeys, they vanished. Their usurpers were the ‘Oh look at me I’m so effin special’ shoestring fry and the ‘I can’t be arsed chopping them up’ wedges favoured by bogans. The insidious return of the bog-standard straight cut, the cut that saw off both the shoestring and the wedge and that now reigns supreme, is not something we should wring our hands over though. There is nobility in its simplicity, a beauty in its utilitarianism. And utilitarianism is the ism that best sums up fish and chips.

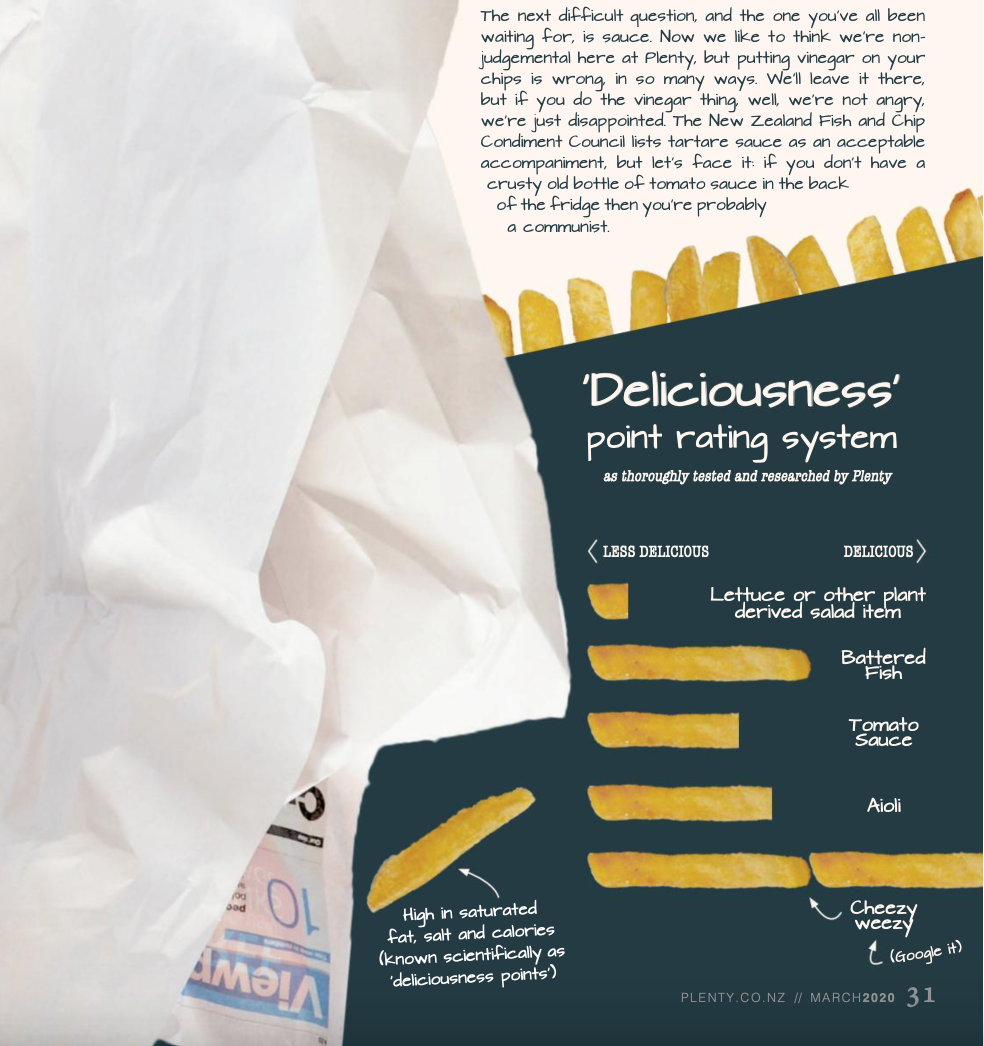

The next difficult question, and the one you’ve all been waiting for, is sauce. Now, we like to think we’re non-judgemental, but putting vinegar on your chips is wrong, in so many ways. We’ll leave it there, but if you do the vinegar thing, well, we’re not angry, we’re just disappointed. The New Zealand Fish and Chip Condiment Council lists tartare sauce as an acceptable accompaniment, but let’s face it: if you don’t have a crusty old bottle of tomato sauce in the back of the fridge then you’re probably a communist.

And that in turn brings us to Kumara chips...

Now, while these are a seasonal fave in certain quarters of the Plenty office, the kumara chip remains an enigmatic choice that comes and goes from fashion like flared trousers and Bacardi rum. Are we wrong? Hands up anyone who says we’re wrong. Yeah? Well you’re wrong. But seriously, the kumara chip remains the elusive unicorn of the deep-fried world; so promising, with the heady mix of sweet and salty, carbs and a crunchy skin, and yet so far this potential has yet to be realised. Is it the thickness, the oil used in frying, the variety of kumara? We don’t know, but it just seems that what should be the perfect marriage made in heaven usually comes over a bit stodgy. Like flared trousers and Bacardi, you tend to look back on kumara chips and wonder what you were thinking at the time. And yet we’re confident that within our lifetime the perfect kumara chip will be achieved, and that’s a further reminder of why it’s great to be alive right now.

Because that’s the great thing about fish and chips: they’ve always been there for us, always in the background, always reassuringly hot, salty and filling, forbidden and yet flirtatiously available when most needed; late at night, just like that hottie friend of your old flatmat who . . . yeah, nah you get the picture.

They were there during the dark days of struggle and strike in the 1930s and 40s, often the only treat for a lot of Kiwis doing it hard, surviving through economic downturn and the legacy of English cuisine, looking forward to fish and chips Friday on a winter Wednesday. They were there for Sir Ernest Rutherford – who wrote passionately of the wedges he and his team enjoyed after fathering nuclear physics – and for Kate Sheppard – who famously celebrated winning the vote for women and making us the first real democracy in the world by shouting battered snapper and two scoops for all the suffragettes. And they were there for ‘The Fish and Chip Brigade’ – David Lange, Michael Bassett, Roger Douglas and Mike Moore, four ‘she’ll be right politicians’ who said yeah nah to the Yanks and made us nuclear free – and for Olympic runner John Walker – the Kiwi flyer who broke the 3:50 mile in Gothenburg in 1975 and famously said his training regime was hard yakka and fish and chips for lunch.

The remarkable thing is that all, well most, of this is true. John Walker really did eat fish and chips before wowing the world in ‘75, we really did tell the US Navy to piss off in ’85, and as long as you run a mile in under four minutes after chowing down on greasies and form a super-power defying government you’re good to go too.

Because isn’t that what fish and chips are all about? It’s sticking it to The Man, it’s living dangerously, it’s knowing the risks and doing it anyway. We had chips long before Ronald ‘invented’ fast food, and by god we’ll guard the Pacific’s triple star from strife and war knowing that on every main street of this great nation any proud Kiwi can walk in and order two fish and a scoop. It’s a Kiwi institution, it’s the way of our people, and it’s bloody yum.